When we rely on statistics to help make important decisions, it’s helpful to know if those stats are actually true. We’ve all heard that most gunfights take place at three yards. It’s part of the old “three shots, three yards, three seconds” standard. But where does that come from? Is it reliable? Do we have any other sources that are more reliable or more specific? Today, we’re taking a critical look at the available data to find out what’s myth and what’s relevant for the average armed citizen for concealed carry.

Details in the video below, or scroll down to read the full transcript.

Hey everybody, Chris Baker here from LuckyGunner.com. A few days ago, we published a video called Do You Need a Red Dot Sight On Your Carry Pistol? It was a kind of overview of some of the pros and cons of pistol optics. Today, I want to do a quick follow up to that video based on some of the feedback I got from you guys.

There was a lot of skepticism about the relevance of optics on defensive handguns. This has brought up a couple of issues that I’ve mentioned briefly in the past, but I think they deserve some more serious attention.

You’ve probably heard the old “Rule of Threes” cliché: the average gunfight involves three rounds fired at three yards in three seconds or less. I want to focus on just the distance part of that for now. That’s the issue that kept coming up in the comments in the last video. And not everyone was saying 3 yards. Some people said 3 yards or less. Or 3 feet. Or 20 feet or some other arbitrary distance for the typical gunfight.

Throwing out these numbers as objections to the usefulness of pistol sights is not a new thing at all. The argument usually has two parts. The first is something like, “if I have to use my gun to defend myself, it’s very unlikely that I will need to take a shot beyond X yards.” And then that’s followed by either “I don’t need to use the sights/red dot/laser at that range,” or “I won’t have enough time to use sights at that range.”

I’m not out to sell anybody on using a red dot optic. There are plenty of good reasons to use one and plenty of good reasons to skip it. But it’s hard to even have a conversation about it if we are all working from different sets of facts. It’s kind of a waste of time to discuss the merits of various types of sights for concealed carry if, for example, you think all gunfights happen at three feet and I think they all happen at 30 yards.

So I want to dive into two questions. And this is actually going to end up being two separate videos. Today, I want to answer “At what distance do defensive shootings actually take place and how do we know that?” And next time, I’ll try to answer “at what range do sights become a relevant part of the equation?”

FBI Statistics

If we assume that there is some truth to the Rule of Threes, we should probably ask where that comes from. The oldest source I’ve seen for the original quote is from Lt. Frank McGee of the NYPD in the 1970s. Today, most people seem to cite the FBI as the source. But the FBI doesn’t actually have any stats on defensive shootings by armed citizens. They do track some data about justifiable homicides, which isn’t quite the same thing, but that does not include any information about engagement distance. Local law enforcement agencies don’t generally document that kind of thing either.

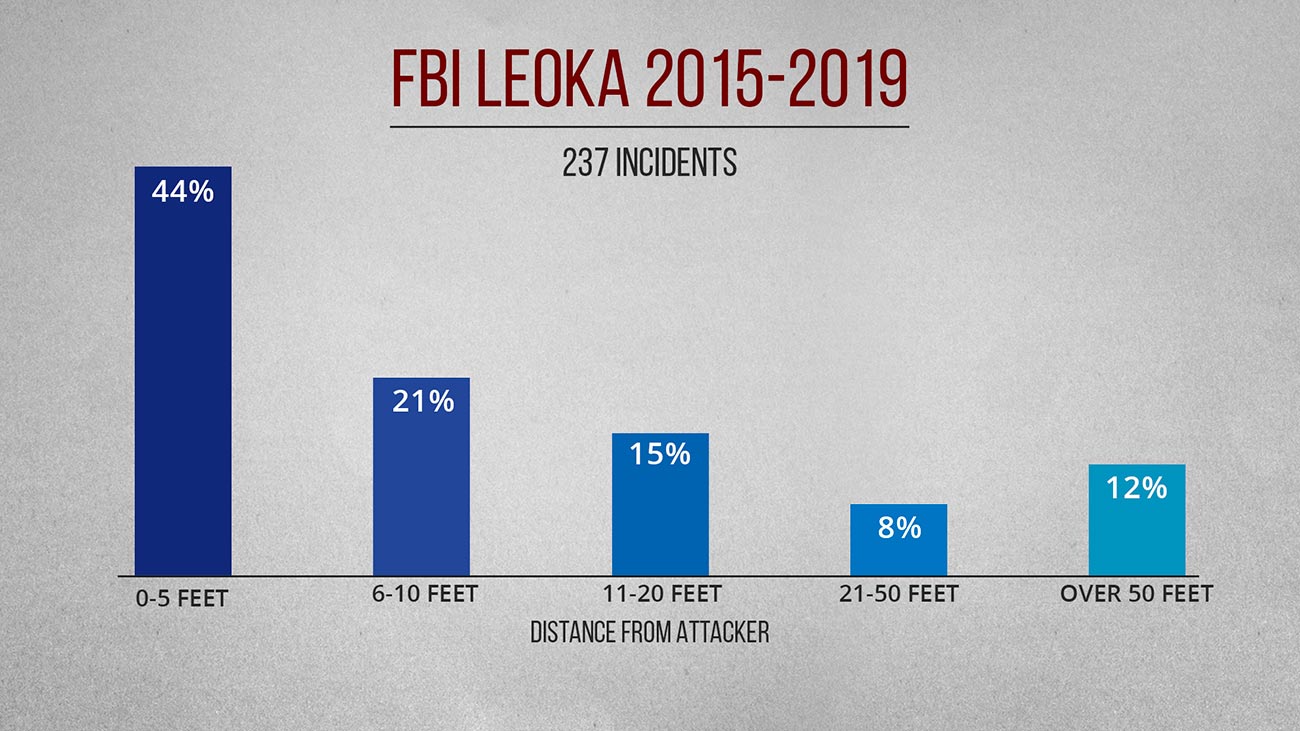

The information we do have on armed citizens is mostly gathered from a variety of unofficial sources. So when people mention actual statistics on engagement distance, they’re usually referring to law enforcement shootings. The most commonly used source is probably the FBI’s report on Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted or LEOKA. That’s part of their annual Uniform Crime Report, which collects stats from law enforcement departments all over the country. There is a table in there that shows the distance from the officers to their attackers when they were killed. I’ve got a graph here of the data from 2015 to 2019.

There were 237 incidents in that five-year period. 44% of those officers were killed at zero to five feet. 21% were killed at 6-10 feet. 35% were at more than 10 feet.

So, if we interpret six to ten feet as being roughly “around three yards,” 21% of the incidents are consistent with the Rule of Threes. If your version of the Rule of Threes is “three yards or less,” that number jumps to 65%. Either way, the problem is that stats for law enforcement killed on duty are a really poor substitute for armed citizen defensive encounters. If I was trying to build a winning football team, I wouldn’t learn much from looking at the stats of games lost by a basketball team.

Even for law enforcement, the FBI numbers only tell a fraction of the story. They don’t say anything about the distances for the police shootings where officers were not killed. It really just tells us that when an officer is attacked, it’s more likely to become deadly if their attacker is very close. No surprise there.

Law Enforcement Statistics

If we want to see engagement distances for officer involved shootings in general, we have to look at the data from individual departments. A few of them have published that information publicly. Let’s look at a couple of the big ones: the LAPD and the NYPD.

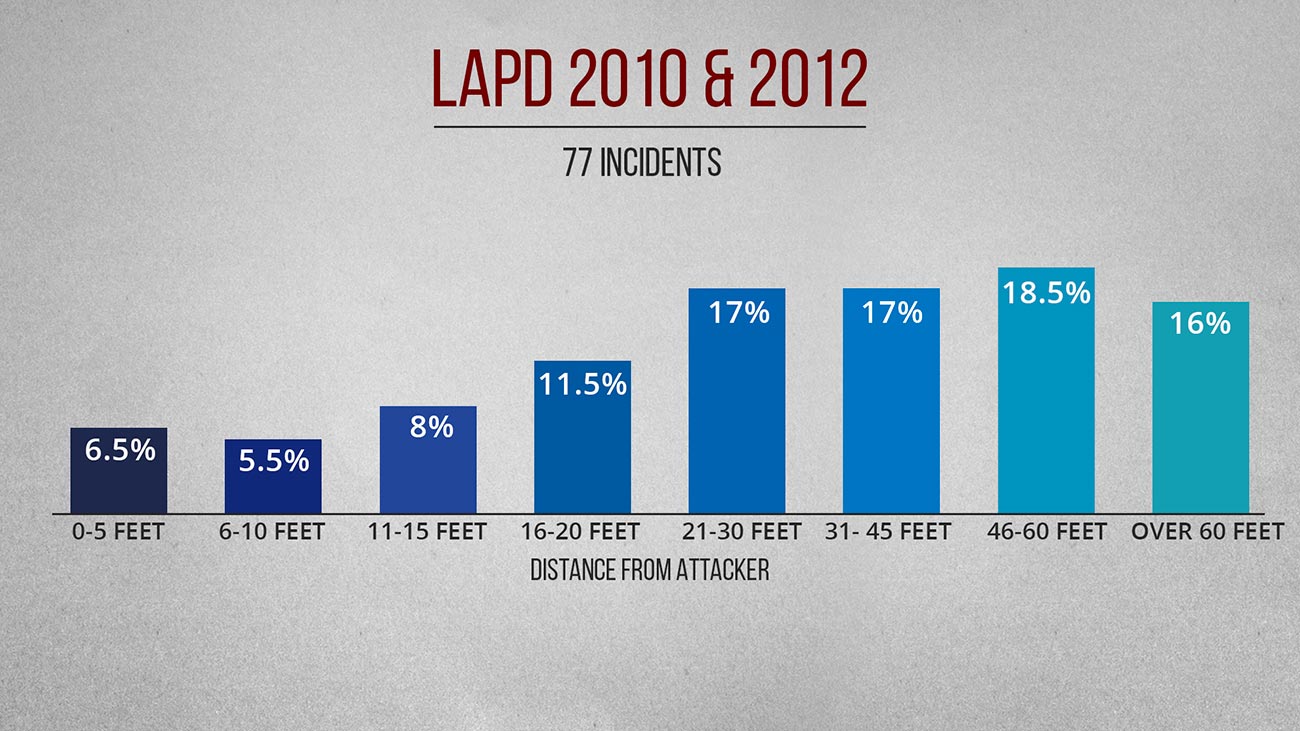

The LAPD included distance in their 2010 and 2012 annual use of force reports. That covers a total of 77 shooting incidents.

Here, we get a completely different picture than what we saw with the FBI’s report. We’ve got a relatively even distribution of incidents from 0 feet all the way out to 60 feet and beyond. Only 5.5% of these fall into that 6-10 foot range. That’s a lot less than the FBI’s 21%.

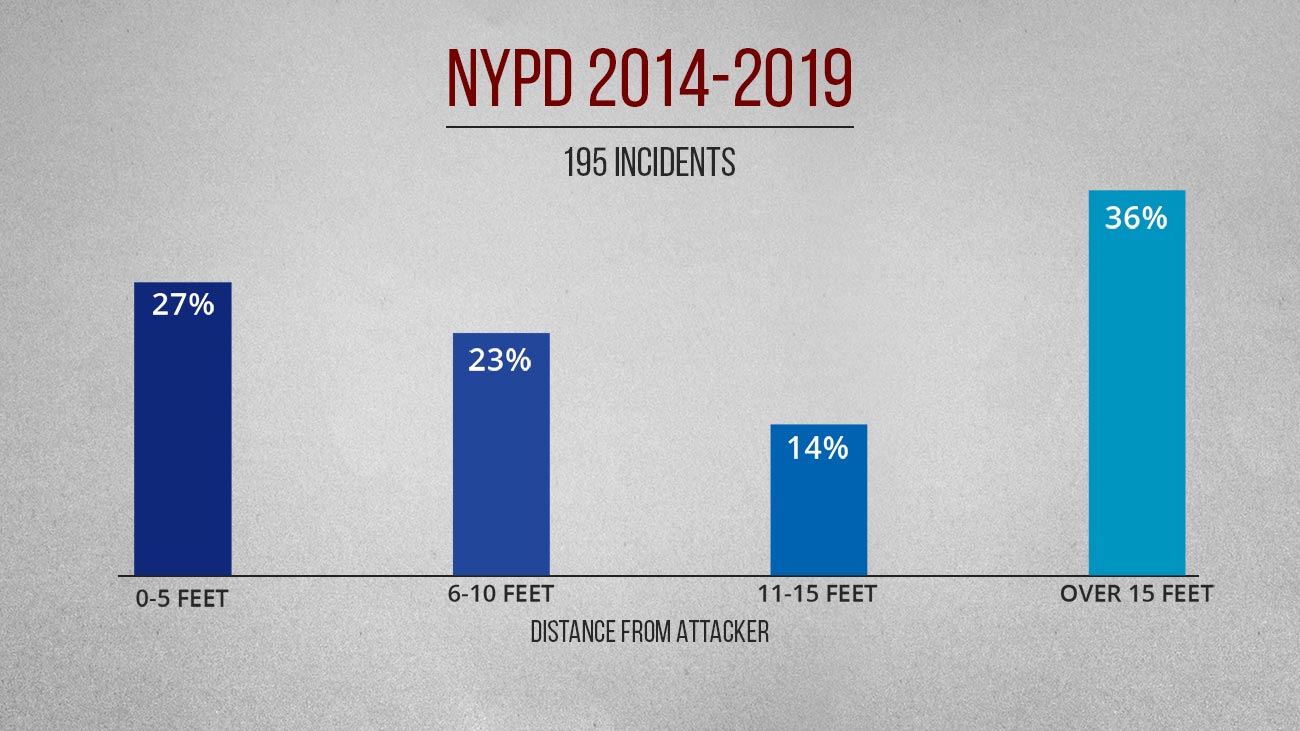

The NYPD includes engagement distance in every year of their annual reports. Here are the average distances from 2014 to 2019. That covers 195 shootings with a known engagement distance.

The NYPD’s data only goes out to 15 feet. Anything past that is all lumped together. Their 6-10 foot numbers are much closer to the FBI data at 23%. But the rest of their numbers are much different.

So we haven’t even looked at any numbers for civilian defensive encounters yet and we’re already seeing quite a bit of variation between sources. It’s also difficult to compare these numbers because they all use different distance increments. And there’s no telling how they’re coming up with these measurements. Distance tends to change really quickly in gunfights, so we don’t know if this is the range where they started or where they ended or just a rough estimate based on the officer’s recollection.

Engagement Distances for Armed Citizens

I’m always reluctant to draw conclusions for armed citizens based on law enforcement data anyway. Cops are supposed to find and apprehend violent criminals. Private citizens should be trying to avoid and break contact with violent criminals. Those stats include incidents where the cop already had their hands on a suspect to arrest them when things turned violent. Or they were ambushed at a traffic stop. Those types of encounters would skew our numbers if we’re trying to get an idea of what threats the law abiding citizen might typically face.

It is notoriously difficult to find actual data on civilian-involved defensive shootings, especially if you’re looking for details like engagement distance. There is a lot of anecdotal evidence to suggest that the range of three to five yards is typical. Firearms instructors who have attempted to study this stuff will frequently throw out numbers around that range.

For example, John Correia from the Active Self Protection YouTube channel has watched thousands of gunfight videos and he’s mentioned the three to seven yard range as the most common. Claude Werner (aka The Tactical Professor) did an analysis of several years’ worth of stories from the Armed Citizen column in The American Rifleman. His summary on distance was that the majority of the incidents were “slightly in excess of arm’s length.”

Claude has also been studying off-duty shootings by LAPD officers. These incidents are documented and made public just like on-duty shootings, but the circumstances are essentially the same as what the average armed citizen might face. These are people in civilian clothes being randomly targeted by criminals. Claude has found that nearly all of those incidents conform to the three yards, three shots, three seconds generalization.

Rangemaster Student Database

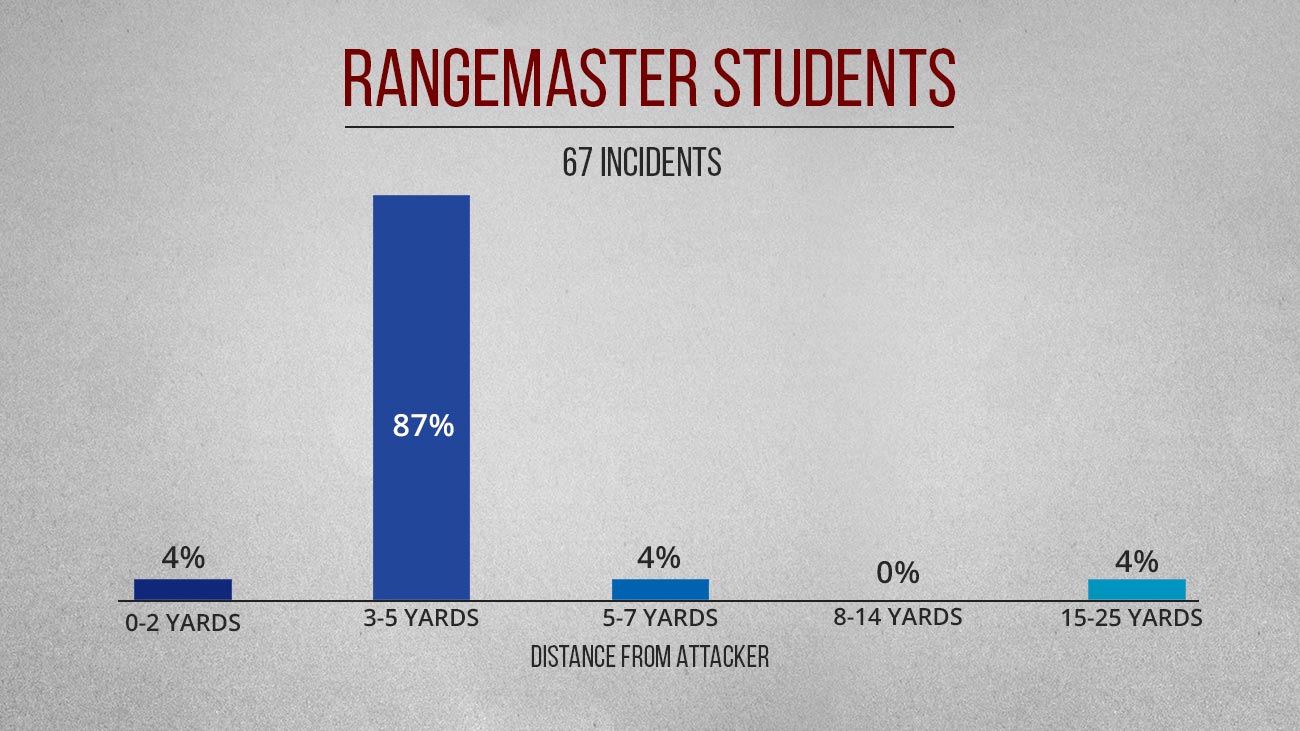

The best resource that I’m aware of that has actual numbers I can put on a neat little graph for you rather than general impressions comes from Tom Givens of Rangemaster Firearms Training. Tom has been teaching defensive shooting classes for several decades. He keeps a database of all of his past students who have been involved in shootings. The best place to find his most recent commentary on those events is in his book Concealed Carry Class.

So far, there have been 67 incidents with shots fired involving his former students. Three of those students were killed because they were unarmed at the time of the attack. The other 64 fought back and survived. Only three had minor injuries and none of them were convicted of any wrongdoing.

4% of those shootings took place at zero to two yards with minor physical contact occurring in a couple of those. 87% were between three and five yards. 4% were at five to seven yards, and another 4% were all the way out at 15 to 25 yards.

Tom’s explanation for these numbers is that most civilian incidents involve armed robbery or sexual assault. Violent criminals typically attempt to threaten and scare victims into compliance when they’re still a safe distance away. That’s outside of what most of us consider our personal space. Once it’s clear the victim is going to do what they say, the attacker will move in closer.

Keep in mind, these are all former students of Tom Givens, so by definition, they’ve all had at least one or two days of really solid training. If we had a data sample from the more typical untrained masses, the numbers might look a little different. I suspect, with an untrained population, people might be a bit slower to react and we’d probably see a greater share of encounters in that 0 to 2 yard range.

That said, if we look at all of the stats we do have, civilian and law enforcement, flawed though they may be, and combine them with the anecdotal evidence that’s out there, the range that seems to come up most often is somewhere between 3 and 5 yards. Incidents do happen that are closer and farther out. But we should probably prioritize our efforts to deal with that three to five yard problem.

So, that leaves us with our second question. Are sights actually necessary or useful at three to five yards? And is using the sights even feasible in such a short time frame? That’s what we’re going to look at next week. Until then, be safe and don’t stop believing. Just hold on to that feeling.

The post The True Distance of a Typical Gunfight appeared first on Lucky Gunner Lounge.